Final paper for my class on emerging diseases:

The longer I spend studying emerging diseases, officially or recreationally, the more I am convinced that hype will be the death of us. Forget bird flu, mad cow, super bugs, frankenfoods, or whatever clever nickname the media comes up with next. We’re actually all going to drown in a sea of clever nicknames.

In all seriousness, science is in more peril of death through over-hyped politicians than the average American is through disease emergence. Fear-mongering among infectious disease researchers, each looking for more government grants and pharmaceutical studies, is an emerging threat. As the case of Thomas Butler forebodes, infectious disease research is becoming both more lucrative and more fraught with danger. (Disclaimer: my MS is being funded by a USDA grant thanks to the surge in funding available in biosecurity.)

For

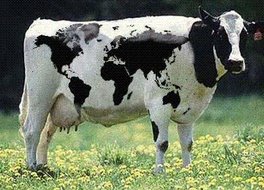

That is the American (and, to some extent, European) reality. The situation in the developing world is much closer to horror than hype. With the near complete lack of diagnostic capabilities, government interest, control or surveillance, the majority of the global population is living in a time bomb waiting to explode. If the developed world is at risk, it is from the incubation potential in the developing world.

Where are we going? If things continue as they do, with funding pledged but not delivered, with isolationism and protectionism, with ignorance and complacency, the future does not look bright. The systems we are building with social, economic, and technological inequity will not protect us; they will eventually be broken down by the transboundary nature of the most serious infectious diseases. Unless changes are made, pandemics will become a regular but unpredictable reality.

What changes could protect us? Giving teeth to the only organizations with a presence in international disease control (WHO, OIE, FAO) would be a good start; the voluntary nature of the current system is unsupportable when diseases are mandatory. Fully funding even a tenth of the surveillance programs in existence would also be a strong step forward; the protections we have in place won’t work without supplies and staff. The most important move we could make, though, is to encourage education. Strong scientific education in the developed world would most likely result in a public that cares about funding disease research and control. Health education in the developing world could make a dent in the behaviors that breed epidemics. As the world understands infectious diseases better, infectious diseases have fewer chances to emerge and spread.

No comments:

Post a Comment